end stage liver disease death process

Department of Surgery - End-stage Liver Disease (ESLD)

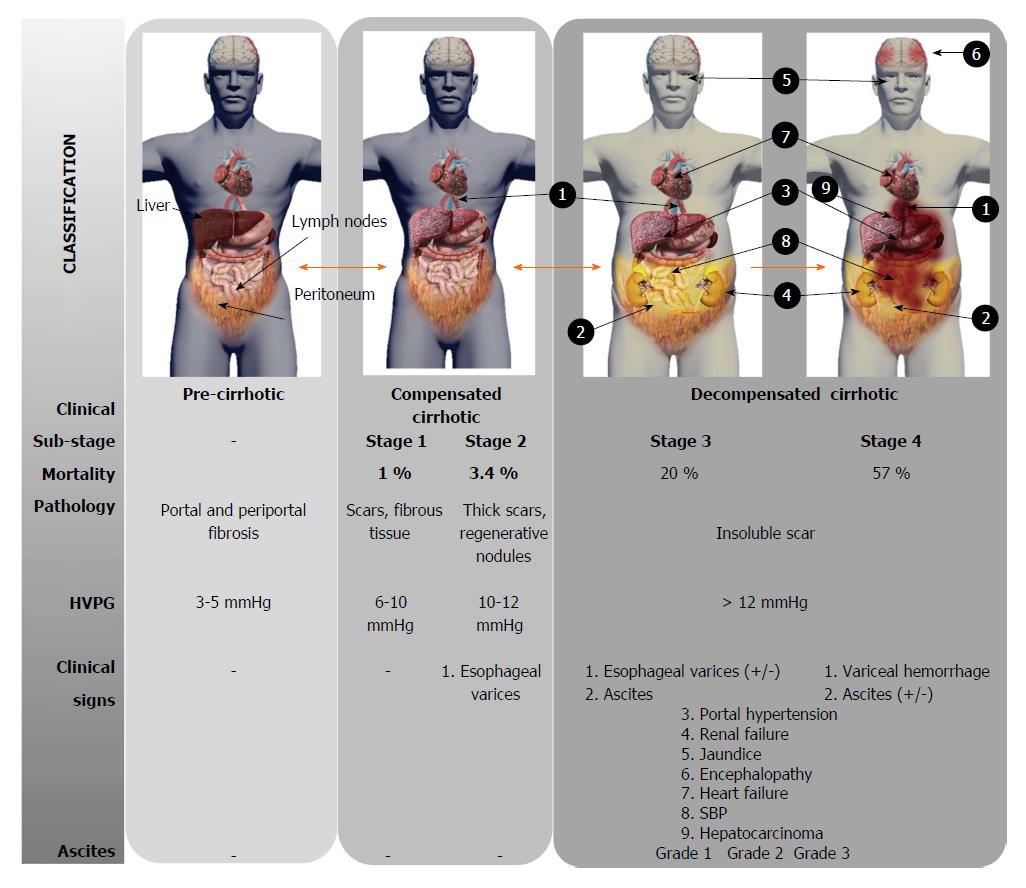

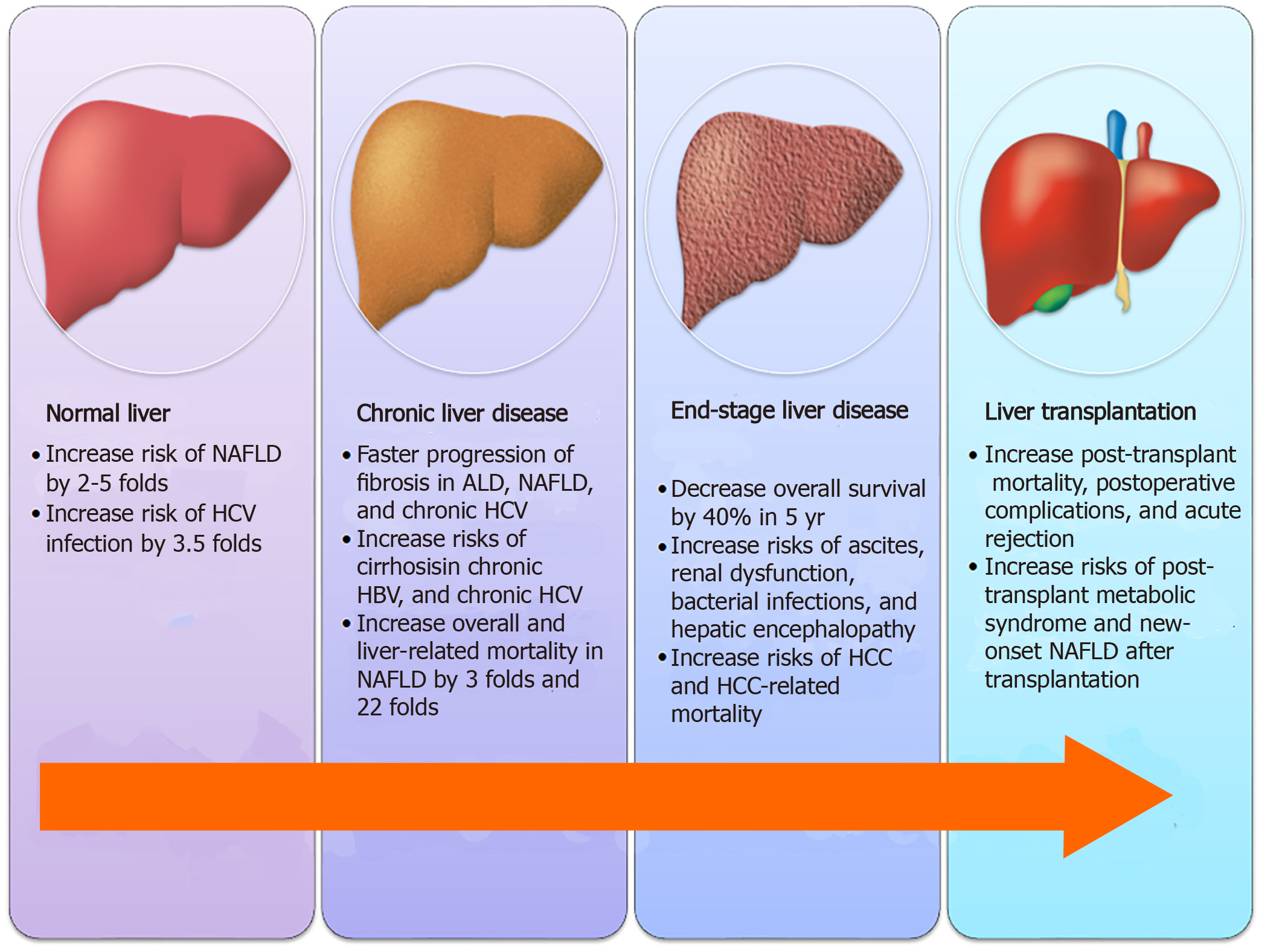

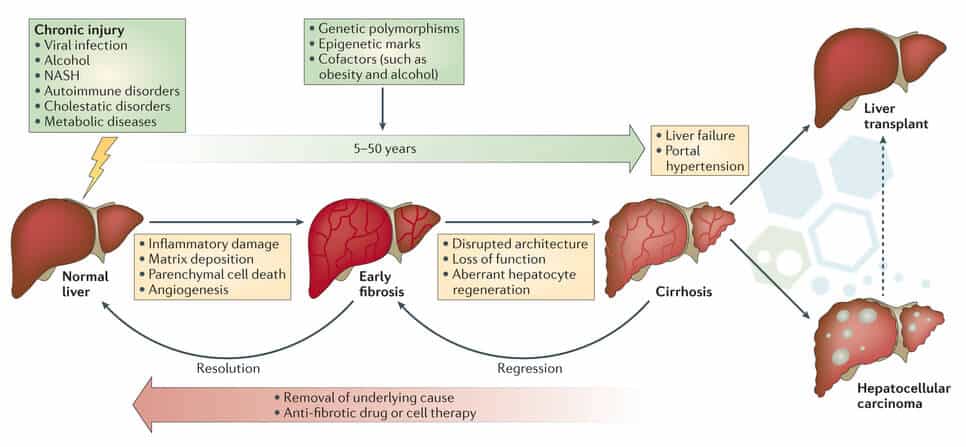

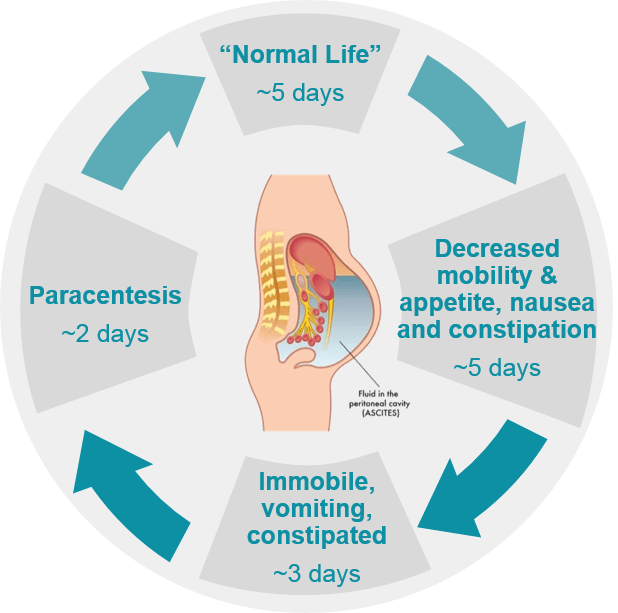

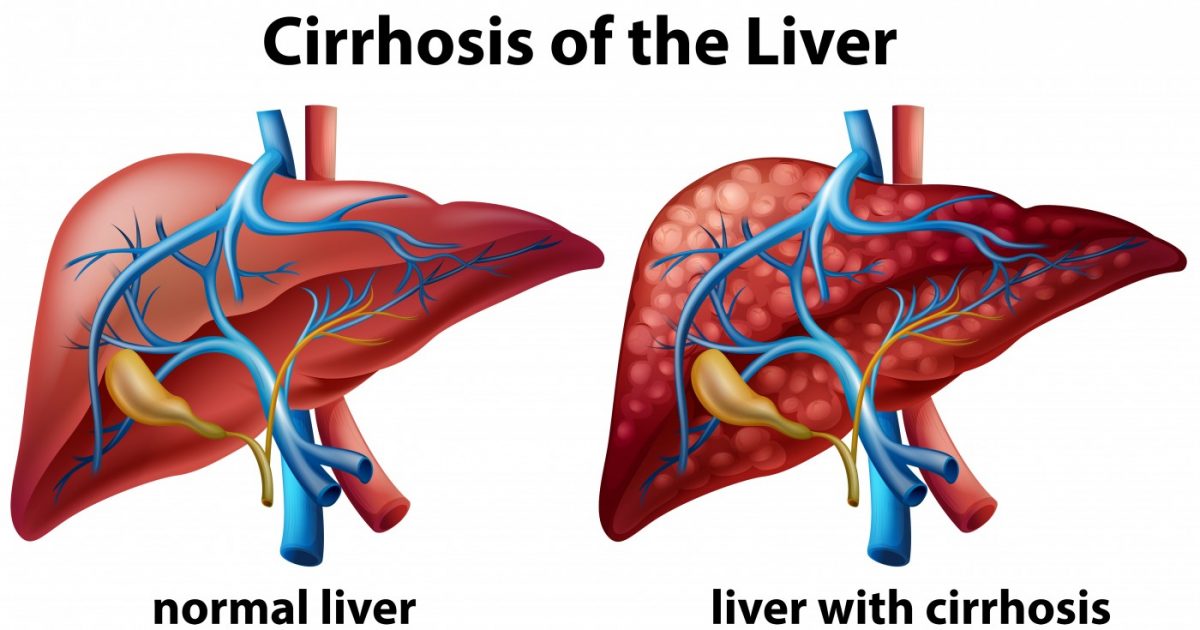

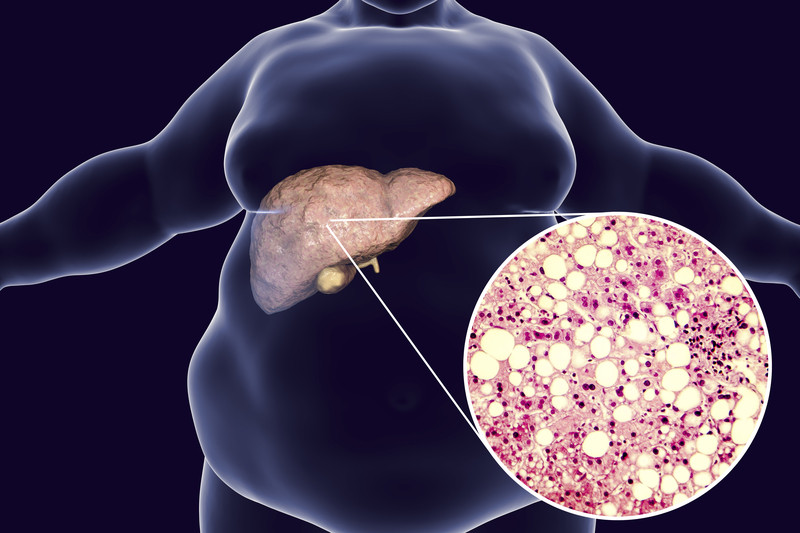

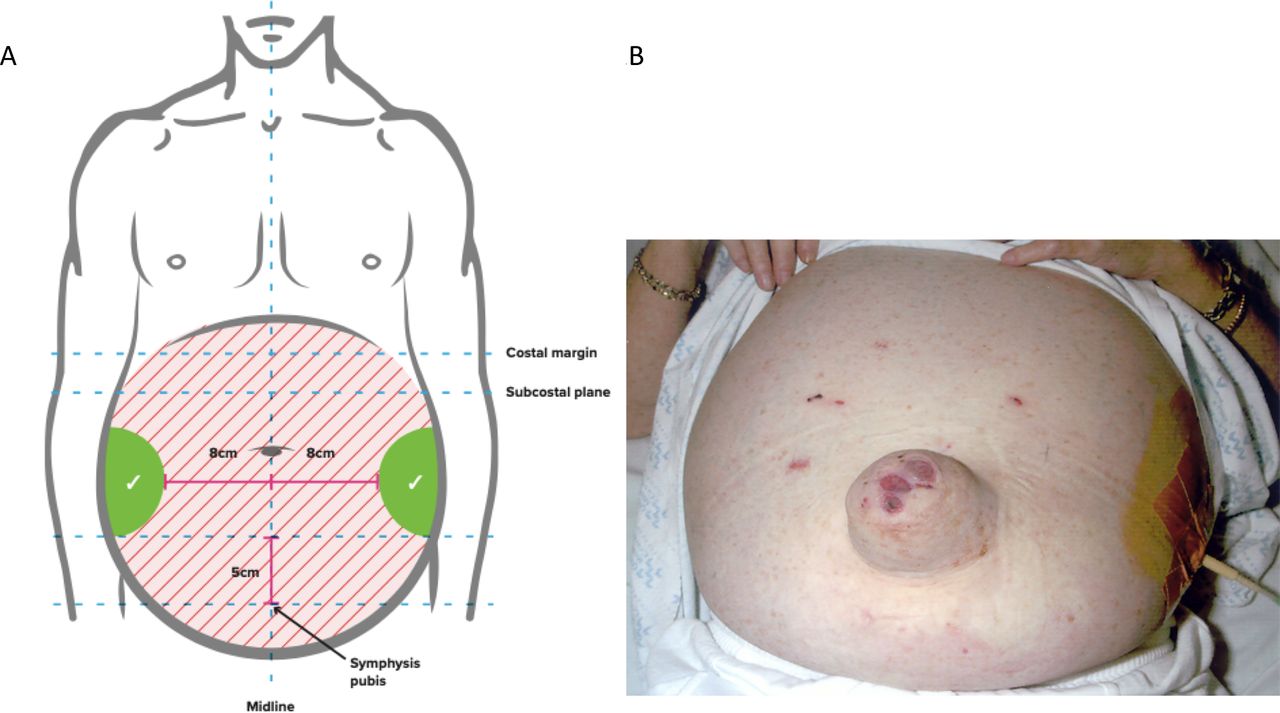

Department of Surgery - End-stage Liver Disease (ESLD)Warning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. Integration of palliative care in end-stage liver disease and liver transplant Jamie Potosek1Hematology/Oncology Department, Regional Providence Cancer Center, Lacey, Washington. Michael Curry3Department of Gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. Mary Buss2Hematology/Oncology Department, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. Eva Chittenden4Division of Palliative Care, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. Patients with end-stage liver disease (LDS) have a life-limiting disease that causes multiple symptoms of anguish and negatively affects quality of life (QOL). This population has traditionally not had much attention in the palliative care community. Discussion: This article provides evidence-based review of palliative care problems that patients with STDs and those who expect liver transplantation, including prognosis approaches, symptoms management, early care planning and end-of-life care. Conclusion: There is a tremendous opportunity to integrate palliative medicine into the care of these patients. IntroductionThe intermediate stage liver disease (ESLD) is a synonym for advanced liver disease, liver failure and decompensated cirrhosis. It is a progressive disease that develops after inflammatory changes in the liver lead to fibrosis and disruption of the structure and function of the liver. The only existing cure is liver transplantation, an option that only a minority of patients will receive. The remaining therapies are palliative in nature. ESLD is a terminal diagnosis, one that can cause symptoms such as pain, fatigue, abdominal pain secondary to ascites and confusion. Quality of life (QOL) is often negatively affected by such physical symptoms, as well as by psychological complications of the disease. According to the relatively poor prognosis, the symptom and the prevailing mental health problems faced by patients with EDSL, this group would benefit greatly from better collaboration between palliative doctors, hepatologists and transplant surgeons. To date, ESLD has received relatively little attention in the palliative care community. Meanwhile, DDSD is increasing in the United States; it is estimated that 5.5 million people, 2 per cent of the population, are affected. More than 2 million clinical visits, 500,000 hospitalizations and 40,000 deaths occur annually. These statistics, promoted by the International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition codes (ICD-9), probably underestimate the real burden of the disease. The most common causes of SCD in the United States are alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C. Obesity is associated with a spectrum of liver disease of liver stoatosis (hypatic fat) to more severe liver damage known as nonalcoholic stoatohepatitis; both can lead to cirrhosis and ESLD. This problem is on the rise and is expected to become the main reason for liver transplantation between 2015 and 2030. The liver transplant leads to a major survival advantage, but it is achievable for a minority of patients. Of the 16,000 patients on the waiting list, 6500 are transplanted annually, while 1600 patients will die pending annual transplantation. Many more are removed from the waiting list as they get too sick for the transplant. This article summarizes the available literature based on evidence of palliative care and ESLD. A search for MEDLINE databases was carried out with the headings of the topic "last stage liver disease", "cirrhosis" or "life transplant", and "palliative care", "Prognosis", "symptom management", or "supporting quality". Additional studies were located by manual search using references of recovered items. The Experience of ESLD Patients Patients with ESLD can present in various ways. Commonly, a asymptomatic phase of offset cirrhosis progresses to portal hypertension followed by decompensation to ESLD. Complications of portal hypertension include ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, esophageal and gastric varices, liver encephalopathy, kidney failure and coagulopathy. Symptoms often include fatigue, abdominal swelling and pain, spontaneous bruising, gastrointestinal bleeding, and confusion. Syntomatic and QOL ExperienceThere are few studies that examine the perspective of patients living with ESLD and those suffering from liver transplantation. A study based on Korean questionnaires of 129 cirrhotic patients identified fatigue, abdominal distaste, peripheral edema and muscle cramps as the most often needed symptoms of management. Eighty-eight Australian patients with chronic hepatitis C were surveyed and 83% reported 6 or more symptoms in the last 3 months, with physical and mental fatigue, irritability, depression and abdominal pain being the most common reported. The SUPPORT study reported that 60% of STD patients identified experienced pain. This was valued at least moderately severe most of the time in 1 of 3 patients. Often there is a discrepancy between the patient's burden of symptom and the medical awareness of such symptoms, for example, muscle cramps, which occurred in 52% of the 92 cirrhotic patients in a 1996 survey, are not often identified as a medical problem. Several questionnaire-based studies have shown a decrease in all aspects of QOL in patients with EDSLD compared to controls. The earliest age, muscle cramps and hepatitis C have been associated with each with worse QOL, while the severity of the disease has not been shown to correlate. The worst QOL experienced by STD patients is comparable to those with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or heart failure. Patients waiting for liver transplant have a perceived QOL similar to those waiting for heart transplant. In a study of 67 French patients evaluated before and after the transplant, patients reported fewer symptoms related to the disease and a lower overall level of anguish later. QOL after the transplant approached but did not match the general population. Psychiatric Factors It is believed that psychiatric comorbidities are very common in patients with STDs. An Italian survey of 156 patients with cirrhosis found over 50% had a Beck Depression Inventory indicative score of a depressed mood. Those with depression experience experience experience more physical symptoms, have worse QOL, and are more likely to die while waiting for the transplant. This discrepancy is not explained by the severity of the disease. Just as patients with cancer, diagnosing depression can be difficult because of frequent overlap of somatic symptoms such as fatigue, lethargy and insomnia. Anxiety also prevails, with estimates in pretransplant patients ranging from 27% to 44%. A survey of Brazilian patients found 19% to have moderate anxiety levels, while 27% of those who had autoimmune cirrhosis had severe anxiety., PrognosisPatients with compensated cirrhosis have a median survival of 6 to 12 years. Decompensation occurs at 5%–7% per year; median survival decreases to 2 years., Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) and Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores are the most used tools for prognosticism. CTP uses total values of bilirubin, albumin and international standardized ratio (INR), as well as the degree of encephalopathy and ascites. Category A, B and C indicate a growing severity of liver disease. The CTP score was used for the first time in the prognosis and list of candidates for liver transplants; its use has now been validated in patients with liver disease of varying severity. MELD uses INR, bilirubin and creatinine to predict survival; higher scores reflect a more significant liver disease. The United Network for Sharing Organs (UNOS) now uses MELD for the allocation of liver transplants. shows survival rates of 6, 12 and 24 months in ESLD compared to CTP and MELD scores. The clinical trial, the comorbidities of patients, the declination rate and the probability of transplantation should also affect the prognosis in the UNCCD. Table 1.Survival of patients with end-stage liver disease based on Child-Turcotte-Pugh/Model for end-stage liver disease scoresCTP6 months12 months24 months MELD score6 months12 months24 months Class An/a95%90%0-9 Class Bn/a80%70%10–1992%86%80% The prognosis in the UNCCD is comparable to patients with other types of organic insufficiency. Those with heart failure have a survival of 50% of 5 years; class IV heart failure involves 30%-40% of 1 year mortality. Patients with outpatient COPD with the lowest lung function scores have 25% 2-year mortality and 55% 4-year mortality. Asctions are often the earliest complication of the UNCCD; when present indicates 50% 2-year mortality. Median survival is 6 months when ascites become refractory. Severe or refractory encephalopathy has an average survival of 12 months. In an analysis of 178 studies, 30% of patients with STD infections died within 30 days, another 30% within 1 year. Kidney failure has the worst result; hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is equivalent to a rapid deterioration of kidney function in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Declining liver function is believed to cause changes in renal blood flow and blood vessel tone instead of direct kidney damage. Type 1 HRS is quickly progressive, with a median survival of four weeks. Type 2 HRS is more insidious, with a life expectancy of 6 months. It outlines median survival according to the presence of several common complications of the ESLD. Average survival in months for patients with end-stage liver disease (LDS). Transplantation The experience of waiting for a transplant greatly affects patients. Most patients interviewed in qualitative studies experience suffering of a physical and psychological nature. They identify difficulty in coping, loss of confidence in doctors, and medical, personal and social uncertainties. There is little literature about the experience of patients who are not eligible for transplantation. A recent review of the retrospective graph of 102 patients removed from the list of transplants or denies were performed in a single Canadian institution. This study found that although most of these patients had symptoms such as pain and nausea, only 10% of the patients referred to palliative consultations, and 28% had documentation of a do-not-resuscitated state (DNR). This highlights the discrepancy between palliative care needs and utilization. Infraserved groups that have not had the same list for transplants, such as women, minorities and patients with comorbidities, may also represent areas of opportunity for palliative care. Substance abuse is common and transplant programs require withdrawal before listing. Patients in methadone maintenance programs have a high risk of relapse after transplantation. The care of this population with the abuse of co-existing substances can be a challenge and requires close collaboration among doctors. Symptom ManagementIntensive symptoms management is an integral role for palliative care in many diseases. The proper selection and dosage of medicines in ESLD is often difficult. Most drugs are metabolized in the liver and liver failure can lead to the accumulation of toxic drugs or metabolites. The decrease in blood liver flow leads to slower drug metabolism and increased bioavailability. This amounts to increased risk of adverse effects and often leads to less aggressive symptoms management. Clinical trials routinely exclude patients with hepatic dysfunction, making it difficult to apply results to patients with STDs. An examination of the medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2005 found only 23 medications with recommended dose adjustments for liver impairment based on Child-Pugh scores. Patients with STDs report similar pain levels as patients with lung and colon cancer. However, pain abuse is common. No randomized trials or large epidemiological studies of pain management in the UNCCD have been carried out, and data are limited to small case series and preclinical data. Doctors may be reluctant to prescribe opioids for those with a history of substance abuse. Opioids may precipitate or worsen liver encephalopathy and some sources recommend against the use of opioids in patients with a history of encephalopathy. Constipation is a common side effect of opioids and can exacerbate encephalopathy. Despite these limitations, opioids may be required for the management of moderate to constant pain, especially at the end of life. When used, it is generally recommended to initiate at low doses and slow dosage intensification. Removal of morphine in cirrhotic patients is delayed by 35%–60% in studies using single doses management. It is given orally, it increases bioavailability due to the decrease in the metabolism of the first steps. It is recommended to reduce dosage and increase dosing intervals. Morphine should be avoided in patients with concomitant renal dysfunction due to the risk of neurotoxicity due to the accumulation of toxic metabolites. Oxycodone and hydromorphone have also undermined removal profiles in the UNCCD. A study of the administration of single-dose fentanyl in cirrhotic patients did not lead to the alteration of pharmacokinetics. Some have therefore recommended that they be opioids of choice in the UNCCD. Methadone was not altered in a study of 14 patients enrolled in the maintenance of methadone, however, it has not been researched for use as analgesia in patients with liver disabilities. Medicines for free-sale pain are widely used, although guidelines for patients with liver disabilities are not available. Short-term use of acetaminophen at a dose of 4 g/d for 13 days showed no adverse effects when 20 patients with stable liver disease were given, including 8 with cirrhosis. For long-term use, experts recommend doses not exceeding 2-3 g/d. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have many adverse effects, including increased risk of kidney failure and hepatorenal syndrome due to prostaglandin inhibition. NSAIDs can also increase the risk of mucous bleeding and interfere with the effect of diuretics, and are therefore better avoided. The controversy over appropriate strategies for pain management in the ESLD is an area that can help reconcile. Ascites are the most common complication of cirrhosis and the most common reason for hospitalization in STD patients; management involves sodium restriction and use of oral diuretics. It was shown that the dietary restriction of sodium to less than 2 g/d and a diuretic regimen of spironolactone and furosemide were effective in more than 90% of patients in reducing ascites to acceptable levels in an randomized study comparing medical therapy to peritoneous coating in 299 patients. Some patients become refractory to diuretics and require repeated or repeated paracents of transjugular intrahepatic portosis (TIPS). Five meta-analysis in randomized controlled trials available, including 305-330 patients concluded that TIPS led to lower rates of recurrence to ascites but higher rates of encephalopathy. A meta-analysis showed a trend towards improved survival and a second showed a survival advantage for TIPS. For patients who do not submit to TIPS, repeated paracents of high volume are often required. Peritoneal catheters are sometimes used for patients with malignant ascites, retrospective studies have shown a low rate of median infection of 5.9%. However, these catheters are used less often in ESLD because there is a theoretically higher risk of peritonitis. A retrospective review of 12 patients with LCD undergoing catheters placement for refractory ascites resulted in an infection rate of 16%. The continuous peritoneal drainage technique of ascites was studied in 40 patients with STDs and refractory ascites. When they were limited to 72 hours of drainage, there were no cases of infection. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a neuropsychiatric syndrome that spans from subtle personality or sleep disorders to confusion and coma. Precipitations include gastrointestinal bleeding, infections, kidney and electrolyte alterations, constipation and medications, especially benzodiazepines. Treatment involves the correction of the underlying causes and the use of medicines aimed at reducing intestinal toxins, in particular ammonia. Non-absorbable dysaccharides, such as lactulosa, have traditionally been the pillar of treatment. A Cochrane Review of 10 studies of lactulose versus placebo found that only nonrandomized, controlled trials showed a benefit for lactulose in the acute treatment of HE. A randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo for secondary prophylaxis in 140 patients with HE history showed a decline in recurrent HE from 46.8% to 19.6%. Non-absorbable antibiotics, such as rifaximin, can also be used for HE. A meta-analysis of 8 studies comparing rifaximin versus un absorbable dysaccharides showed that rifaximine was at least so effective in HE treatment, with better results in levels of serum ammonia, mental state, asterixis and improved safety. Rifaximin is, however, a more expensive option, an important consideration in the care of patients with hospice. Early care planning and social support Although the data is scarce, the care and early planning objectives of care seem to be discussed less frequently with STD patients compared to cancer patients. In SUPPORT, 66% of STD patients preferred cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) when asked about the state of resuscitation. In a separate study conducted in three teaching hospitals, 16% of patients with DNR had DNR orders compared to 47% of patients with metastatic lung cancer. Housestaff was less likely to discuss these problems with patients with EDSLD despite the awareness of their poor prognosis. There is an inherent difficulty in discussing early directives with patients seeking healing therapies and DNR orders are often considered controversial for patients waiting for transplantation. Bramstedt, an ethical transplant, argues that in some patients with STDs, resuscitation may be useless and not in the best interests of a seriously ill patient. It is imperative to promptly discuss the goals of care and identify the proxy agents of medical care, as encephalopathy may affect decision-making. Caregiver support is crucial for transplant candidates and the lack of a reliable caregiver can prevent transplantation. Qualitative studies reveal that the caregiver's burden is high, with a significant percentage of pretransplanted and posttransplant caregivers reporting a decrease in QOL, low life satisfaction and a high amount of care strain. In particular, women caring for their children have a higher overload and higher levels of depression than men. In a survey of 61 caregivers, there were higher rates of depression and global burden scores when caring for patients with alcoholic liver disease compared to other etiologies. Opportunities for collaboration between palliative care teams and liver transplantation Best practices for the role of palliative care in STD patients and transplant candidates have not been defined. The fourth edition of the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine contains only three references to liver transplantation and a paragraph on palliative care in liver diseases. The UK's Golden Standards Framework, a guide to care for patients with final stage diseases, including heart, lung, kidney, and neurological diseases, omits liver disease. In a survey of UK gastroenterologists, most had access to palliative care, but less than half referred to a patient within the previous 3 months. The most common reasons for remission were attention at the end of life and the management of symptoms. Similarly, lung transplant doctors favor the idea of integrating palliative care after the transplant, but few refer to it. The interest in the population of liver disease seems to be increasing. The recently published book, Evidence-based Practice of Palliative Medicine, contains two chapters on liver disease detailing the clinical course, symptomatology and treatment considerations., Integration of palliative care in hepatology and treatment of transplantsIntroduction of palliative care for patients with EDSL and those who expect transplantation can be difficult. Many patients feel good for years after diagnosis and develop symptoms of STD abruptly. This allows less time to acquire coping skills needed to face a progressive disease and approach the end of life. End-of-living discussions can be difficult as patients often focus their hope on obtaining a life-saving transplant. Many surgical specialists, such as other clinicians, can think of palliative care as synonyms of end-of-life care. In 2005, the American College of Surgeons published a statement that extends the palliative care needs of surgical patients to include those at all stages of the disease. Support has been increased in the transplant community for the integration of palliative care as demonstrated by this statement at Surgical Clinics in North America: "The fields of transplantation and palliative care have a treasure of experience that is missing in the other that could be exchanged profitably with a great sense of satisfaction for all." Such a statement suggests an opening in the transplant community to initiate a dialogue with palliative care specialists. At present, palliative care and hospice are offered to patients shortly after the removal of the transplant list. This event is often associated with the withdrawal of special attention, feelings of abandonment in patients and death within a few days, without the possibility of optimizing attention at the end of life. A strategy to provide palliative care together with disease-directed therapy while the transplant is expected has the potential to improve QOL, patient satisfaction and reduce hospital income without lowering the chances of transplantation. Participation in palliative care after transplantation is another topic that gains interest. A recent pilot study evaluated the intervention of early palliative care for patients after the liver transplant that required admission to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU). This intervention involved 104 patients and 31 deaths. Increased objectives of discussions on child care and mortality rates and reduced duration of stay in ICU. Communication and family satisfaction were improved, as was the previous consensus on the objectives of care without affecting the mortality of patients. There are several barriers that may need to be addressed so that this integration is successful. There may be a misunderstanding that palliative care is the ultimate care of the life and education of transplant doctors is essential. The education of students in related areas could also increase the participation of palliative care in the management of patients with DDSD., The development of clinical triggers for palliative consultations such as the development of refractory ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or HE that each of them has a poor prognosis. The use of certain clinical factors to initiate care palliative consultations has been investigated in many groups of diseases such as heart failure, and has been shown in the ICU environment to give rise to better results as noted above. Care for the hospice Few patients with failure in the final stage organ are released from the hospital with hospice. In 2003, the ESLD was the fifth non-cancer diagnosis for hospice inscription, which represents 1.6% of patients. Possible reasons for underutilizing the hospice include the belief that the transplant and the hospice are mutually exclusive, and the lack of referral guidelines. Patients with ESLD are referred late, with an average survival of 29 days compared to the overall average duration of the hospital stay of 59 days. The late remission of the hospice puts patients at risk of lowering the quality of care at the end of life. Unfortunately, the use of the guidelines of the National Hospice Organization to identify patients with STDs do not accurately identify patients who died within 6 months. MELD has been used to estimate 30-day mortality in a cohort of 50 patients with high-to-hospice ELSD with moderate correlation between MELD and survival. Therefore, the MELD can be used to estimate 6-month mortality, as well as the eligibility of hospices. This has not yet been achieved in practice. The eligibility of patients on the transplant list remains controversial. Those who support this approach cite the inability to know which patients will eventually receive a transplant, that patients at the top of the list have the greatest need for monitoring and preparation for the end of life, and that hospice services can provide support to patients and families and improve QOL. Others feel that patients waiting for transplants should not benefit from hospice care as they are following healing therapies, hospice services may not cover expensive treatments that these patients often need, and according to Health Financing Administration guidelines, more than 80% of the days of care provided by hospice should be at home. If patients on the waiting list should be enrolled in hospice, the hospice teams would have to recognize that patients will probably remain full code and may require hospitalizations for acute decompensation. A recent retrospective review shows an example of successful co-management of patients waiting for transplantation. In 2000, hepatology and hospice services at UC Davis jointly presented the concept of patient comanage. One hundred and fifty-seven patients with the SCD were admitted to hospice under this innovative program; of these patients, 122 died. Patients had an average duration of 38 days. Six patients at hospice went to successful liver transplant, and four of them had improvements in MELD scores during this time. Hospice staff were successfully trained to manage complicated symptoms at home., In this group, the average MELD score at the time of admission of hospice was 21 and almost all patients with MELD aged 18 and over died within several months. This study highlights that only 5% of the patients listed in this program were subjected to transplantation. Complementary Research Areas Palliative care doctors should aim to help better define the needs and expectations of patients with SDSL and help develop appropriate strategies for managing symptoms. Identification of potential triggers for palliative care consultations and hospice references is another opportunity to improve the care of these patients. Finally, even when patients get to transplant, many are left with a new set of chronic problems and will face mortality again. The early participation of palliative care in the management of pretransplant patients would thus provide posttransplant continuity and could lead to better results for patients and families. Early integration of palliative care can also lead to improved symptoms and QOL, and potentially improve the likelihood of a patient's transplant. Abstract Patients with ESLD have significant palliative needs in terms of physical symptoms and psychosocial aspects of care. These needs are often not recognized among caregivers and are not met later. High-quality data are missing that address many palliative aspects of care treatment in the UNCCD. This patient population represents a unique opportunity to continue researching, educating and collaborating between palliative doctors and transplant providers. It is to be hoped that the integration of care among these groups will lead to a significant benefit among patients, caregivers and transplant teams. Author's disclosure statement There are no competing financial interests. ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Evaluation and Management of End-Stage Liver Disease in Children - Gastroenterology

Department of Surgery - End-stage Liver Disease (ESLD)

Inflammatory status in human hepatic cirrhosis

Liver Disease That Can Kill You

The Stages of Liver Disease - American Liver Foundation

Liver Disease - Pathophysiology of Disease: An Introduction to Clinical Medicine (Lange Medical Books), 7th Ed.

/liver-disease-how-long-to-live-63374_color2-5b95e287c9e77c002c1dd24c.png)

How Long Can I Live With Alcoholic Liver Disease?

How Long Can You Live With Liver Cirrhosis?

Department of Surgery - End-stage Liver Disease (ESLD)

Liver Disease: Symptoms, Treatment, Problems | Narayana Health

Liver Disease Last Days

The Stages of Liver Disease - American Liver Foundation

A cautionary tale about dying of liver disease

Clinical implications, diagnosis, and management of diabetes in patients with chronic liver diseases

Cirrhosis of the Liver Stage 4 | Livers With Life

20 liver failure symptoms with stage 4 cirrhosis

Department of Surgery - Alcoholic Liver Disease

A cautionary tale about dying of liver disease

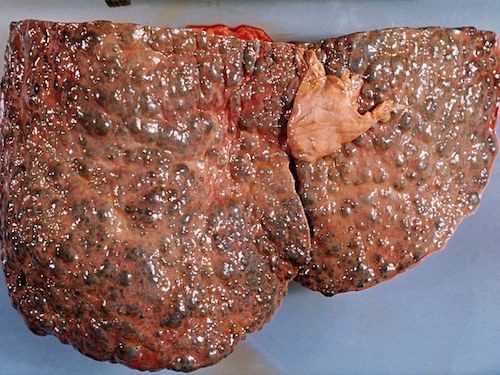

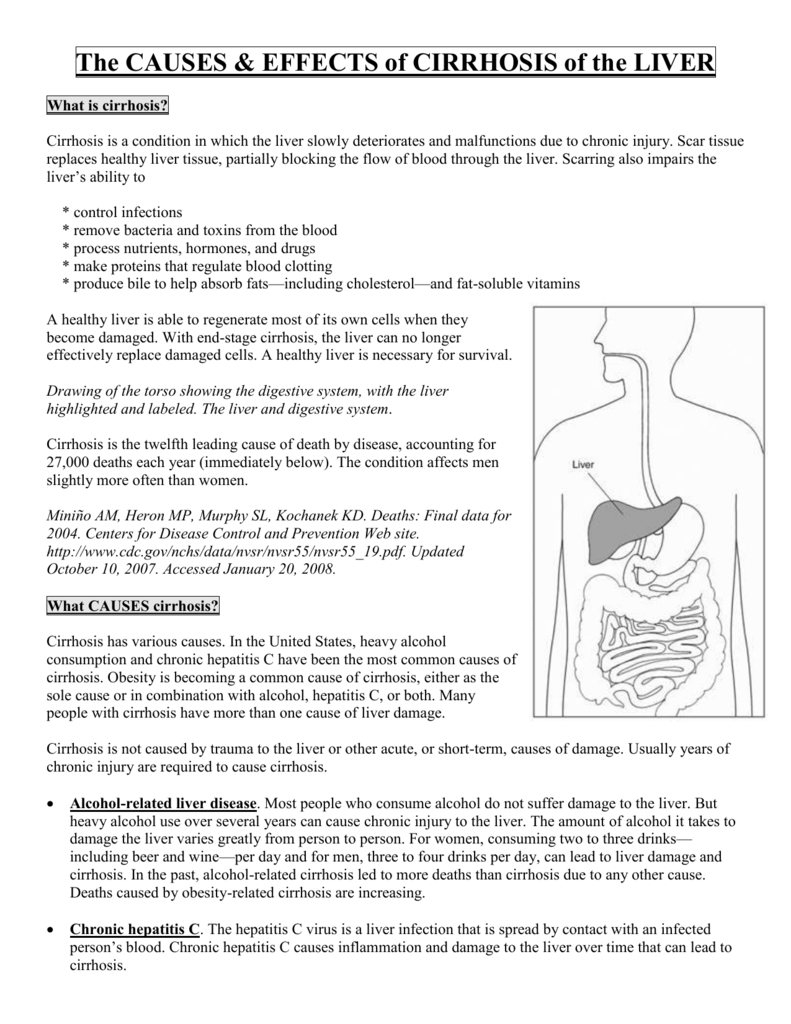

The CAUSES & EFFECTS of CIRRHOSIS of the LIVER

/what-to-expect-in-the-final-stages-of-lung-cancer-2249015-5bc3f30fc9e77c00512feb11.png)

What to Expect During End Stage Lung Cancer

What Is Cirrhosis of the Liver? Treatment, Symptoms, Causes & Stages

Stem Cell Treatment for Liver Disease & Cirrhosis from ARLD

Cirrhosis - AMBOSS

LIVER AND BILIARY DISEASE

emDOCs.net – Emergency Medicine EducationAcute Liver Failure: Evidence-Based Evaluation and Management - emDOCs.net - Emergency Medicine Education

Liver disease (NASH) and Ascites - Sequana Medical

Pulmonary Hypertension and Cirrhosis

Department of Surgery - Alcoholic Liver Disease

Stem Cell Treatment for Liver Disease & Cirrhosis from ARLD

Disparities in Deaths from Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis

When the liver gets fatty - Harvard Health

/male-latin-american-senior-patient-lying-down-on-hospital-bed-looking-away-thoughtful-1141825154-0d3be4f2b5b24ef1809c853ee15c82dc.jpg)

End-Stage Alcoholism: Definition, Symptoms, Traits, Causes, Treatment

Albumin in decompensated cirrhosis: new concepts and perspectives | Gut

Alcohol-Related Liver Disease: Symptoms, Treatment and More

Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis | Gut

/liver-cancer-symptoms-5ae778bd1f4e1300366840a0.png)

Liver Cancer: Signs, Symptoms, and Complications

Case 29-2020: A 66-Year-Old Man with Fever and Shortness of Breath after Liver Transplantation | NEJM

Cirrhosis - Wikipedia

Scottish Palliative Care Guidelines - End Stage Liver Disease

Fatty liver disease: What it is and what to do about it - Harvard Health Blog - Harvard Health Publishing

Posting Komentar untuk "end stage liver disease death process"